|

Valentina Belotti, the first Italian to win the "Empire State Building Run Up": 86 flights of stairs in 12 minutes and 37 seconds.

by Elisa Campisi (Corriere della Sera) The athlete from Brescia, 43 years old, won the women's race, crossing the finish line on the terrace of the New York skyscraper (1,576 steps). Her husband, Emanuele Manzi, finished fourth in the men's race. Third place in the male category an other Italian, Fabio Ruga, She raced up 86 flights of stairs, 1,576 steps. Upon reaching the terrace, with the Manhattan skyline before her, shrouded in the darkness of night and punctuated by lights, she gazed upon a 360-degree panorama of New York, Brooklyn, Queens, and beyond. This is how Valentina Belotti's timed ascent concluded, making her the first Italian ever to win the most famous "towerrunning" race, one that takes place in the building that serves as the backdrop for many film scenes: the Empire State Building. In its 45th edition, the competition consists of ascending the skyscraper. Elite professional runners, some American celebrities, and 300 athletes selected from thousands of aspiring participants can take part. Belotti finished first in the women's category, in 12 minutes and 37 seconds (1,576 steps), ahead of the German Verena Schmitz and the American Shari Klarfeld. The Italian athlete from the Malonno Sports Union thus crowns a career filled with significant achievements. A native of Temù in Brescia and captain of the mountain running national team, the champion has already won towerrunning competitions on skyscrapers in Shanghai, Taipei, São Paulo, Brazil, as well as in Milan on the Pirelli skyscraper and the Allianz Tower. Italy this year, at the Empire State Building Run Up, not only boasts Belotti's victory but also a podium finish in the men's category, with Fabio Ruga in third place, preceded by the Malaysian Wai Ching Soh, who won in 10 minutes and 36 seconds, and the Japanese Ryoji Watanabe. In the top five is also Belotti's husband, Emanuele Manzi, classified in fourth place. A record-breaking couple in a race where no Italian had ever before succeeded in etching their name in the winners' list. |

Over the years, the competition has been won by many world-famous athletes, such as the multiple world mountain running champion Andrea Mayr and the Australian Paul Crake. In 2022, after yet another physical setback, Belotti had contemplated retirement, but her passion for the mountains and running prevailed, and as always, it helped her not only overcome the challenge with herself but also the Vertical Nasego. Four-time silver medalist at the mountain running world championships, from the cross-country races of the Youth Games in the early '90s to the victory in New York, Belotti has accumulated numerous successes and Italian and European titles, but also many injuries. The athlete has always bounced back, and at over 40 years old, she continues to amaze. This latest triumph only confirms the mettle of a true champion.

|

July 18th, 64 AD, when Nero (did not) burn Rome

Alberto Angela has dedicated a trilogy of books to the fire that devastated the eternal city: "Nero Guilty? It was the first and greatest fake news in history."

La Nazione, Florence, July 18th, 2023 (in Italian after this in English)

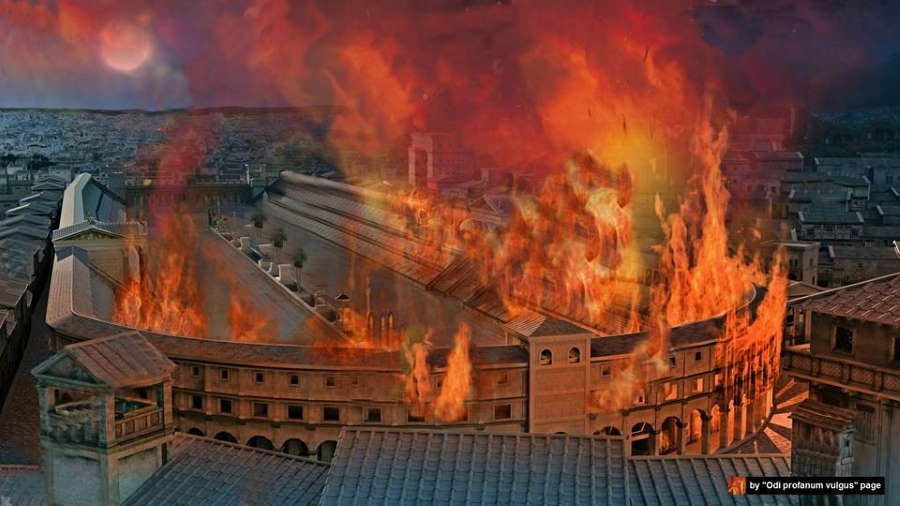

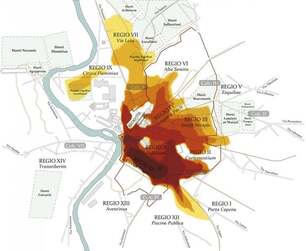

On the night of July 18th, 64 AD, the great fire broke out that forever changed the geography of Rome and our history. But what really happened that day? And was Nero truly responsible? Alberto Angela, a renowned science popularizer, as well as a paleontologist and naturalist, has recounted the catastrophe in a trilogy of books dedicated to the last emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. An emperor portrayed with a dual personality: "The cheerful one, a boy who loved music and speed. There were no motorcycles, but Nero raced with chariots." And the other side is the fierce, cynical one: "He kills his mother, his wife, has anyone who hinders him or whom he suspects may plot against him killed. He is ruthless," Angela recounts. But then you realize that when he dies, others do worse. "Reconstructing the fire of Rome is like writing a detective story," explains Angela. Except the plot is hypothetical yet truthful, and the evidence has turned to ashes for two thousand years. Contrary to popular belief, July 18th, 64 AD, may mark the first and greatest fake news in history: Rome burns, and the emperor is deemed responsible. "It happened in both directions," Angela explains. "Nero unjustly accused the Christians, and he himself became a victim of fake news for history, portraying him as a black, ruthless prince. But neither he nor the Christians were responsible for the fire. Historians agree that the greatest fire in the history of Rome was a case of chance, occurring under precise conditions: scorching hot days in a city almost entirely made of wood. And above all, the spark occurred among the warehouses of the Circus Maximus, Rome's largest wood depot, at night. The next day, the wind blew, and it was the end. Rome burned for nine days. Rome was a city of one million inhabitants. Fires were very common: it is estimated that a severe fire occurred every ten to fifteen years. One thing is certain: the one on July 18th happened at night in an area that was bustling during the day, full of shops, but turned into a seedy part of Rome at night, populated by prostitutes, fortune-tellers, and frequented by drunkards in taverns. It could have been a brawl." Anything but Nero, in short. "First and foremost," Angela emphasizes, "because he had no reason to set Rome on fire, and then because it was not in his interest. It was the city he loved, and he had the support of the people to keep it under his control because, unlike the senators, they were on his side. Could he set fire to the people who ensured his power? And burn down so many things he loved: his palaces, his collections, even the Circus Maximus itself? The sources tell us that, on the contrary, he hurried back from Anzio, where he was at the time, to try to help: he opened his palaces to accommodate the displaced. There is also another fact that is often overlooked: no one could have imagined that by setting fire to a few palaces, the entire city would go up in flames."

Circo Massimo and the destruction after a week.

Alberto Angela has dedicated a trilogy of books to the fire that devastated the eternal city: "Nero Guilty? It was the first and greatest fake news in history."

La Nazione, Florence, July 18th, 2023 (in Italian after this in English)

On the night of July 18th, 64 AD, the great fire broke out that forever changed the geography of Rome and our history. But what really happened that day? And was Nero truly responsible? Alberto Angela, a renowned science popularizer, as well as a paleontologist and naturalist, has recounted the catastrophe in a trilogy of books dedicated to the last emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. An emperor portrayed with a dual personality: "The cheerful one, a boy who loved music and speed. There were no motorcycles, but Nero raced with chariots." And the other side is the fierce, cynical one: "He kills his mother, his wife, has anyone who hinders him or whom he suspects may plot against him killed. He is ruthless," Angela recounts. But then you realize that when he dies, others do worse. "Reconstructing the fire of Rome is like writing a detective story," explains Angela. Except the plot is hypothetical yet truthful, and the evidence has turned to ashes for two thousand years. Contrary to popular belief, July 18th, 64 AD, may mark the first and greatest fake news in history: Rome burns, and the emperor is deemed responsible. "It happened in both directions," Angela explains. "Nero unjustly accused the Christians, and he himself became a victim of fake news for history, portraying him as a black, ruthless prince. But neither he nor the Christians were responsible for the fire. Historians agree that the greatest fire in the history of Rome was a case of chance, occurring under precise conditions: scorching hot days in a city almost entirely made of wood. And above all, the spark occurred among the warehouses of the Circus Maximus, Rome's largest wood depot, at night. The next day, the wind blew, and it was the end. Rome burned for nine days. Rome was a city of one million inhabitants. Fires were very common: it is estimated that a severe fire occurred every ten to fifteen years. One thing is certain: the one on July 18th happened at night in an area that was bustling during the day, full of shops, but turned into a seedy part of Rome at night, populated by prostitutes, fortune-tellers, and frequented by drunkards in taverns. It could have been a brawl." Anything but Nero, in short. "First and foremost," Angela emphasizes, "because he had no reason to set Rome on fire, and then because it was not in his interest. It was the city he loved, and he had the support of the people to keep it under his control because, unlike the senators, they were on his side. Could he set fire to the people who ensured his power? And burn down so many things he loved: his palaces, his collections, even the Circus Maximus itself? The sources tell us that, on the contrary, he hurried back from Anzio, where he was at the time, to try to help: he opened his palaces to accommodate the displaced. There is also another fact that is often overlooked: no one could have imagined that by setting fire to a few palaces, the entire city would go up in flames."

Circo Massimo and the destruction after a week.

18 luglio del 64 d.C., quando Nerone (non) bruciò Roma

Alberto Angela ha dedicato una trilogia di libri all’incendio che ha devastato la città eterna: “Nerone colpevole? È stata la prima e più grande fake news della storia”

La Nazione, Firenze, 18 luglio 2023

Firenze, 18 luglio 2023 – Nella notte del 18 luglio del 64 d.C. scoppiò il grande incendio che ha cambiato per sempre la geografia di Roma e la nostra storia. Ma cosa accadde veramente quel giorno? E fu davvero responsabilità di Nerone? Alberto Angela, celebre divulgatore scientifico nonché paleontologo e naturalista, ha raccontato la catastrofe in una trilogia di libri dedicati all'ultimo imperatore della dinastia giulio-claudia. Un imperatore rappresentato col suo doppio volto: “Quello gioviale, di un ragazzo che oltre alla musica amava la velocità. Non c'erano le moto, ma Nerone andava con le quadriglie". E l'altra parte è quella feroce, cinica: "Uccide la madre, la moglie, fa uccidere tutti quelli che lo intralciano o che abbia il sospetto possano tramare contro di lui. È implacabile" racconta Angela. Ma poi ti accorgi che quando muore lui gli altri fanno di peggio. “Ricostruire l’incendio di Roma è come scrivere una detective story” spiega Angela. Solo che l’intrigo è ipotetico ancorché veritiero, e le prove sono in fumo da duemila anni. Contrariamente a quanto si pensi, Il 18 luglio del 64 d.C. si registra forse la prima e più grande fake news della storia: Roma brucia e l’imperatore è ritenuto responsabile. “È avvenuto nei due sensi – spiega Angela -. Nerone ha accusato ingiustamente i cristiani, e lui stesso è stato vittima di fake news per la storia, che lo ha dipinto come un principe nero, spietato. Ma né lui né i cristiani sono stati i responsabili dell’incendio. Gli storici sono concordi nel ritenere che il più grande incendio della storia di Roma sia stato un caso, avvenuto in condizioni precise: giornate caldissime, in una città che era quasi interamente fatta di legno. E soprattutto: l’innesco è avvenuto tra i magazzini del Circo Massimo, il più grande deposito di legna di Roma, di notte. Il giorno dopo soffiò il vento, e fu la fine. Roma bruciò per nove giorni. Roma era una città da un milione di abitanti. Gli incendi erano facilissimi: si stima che ogni dieci/quindici anni se ne registrasse uno molto grave. Di certo sappiamo che quello del 18 luglio è avvenuto di notte, in una zona che di giorno era molto frequentata, piena di negozi, mentre di notte diventava un bassofondo di Roma, popolato da prostitute, veggenti, pieno di bettole frequentate da ubriachi. Potrebbe essere stata una rissa”. Tutto ma non Nerone, insomma. “Innanzitutto – sottolinea Angela - perché non aveva motivo per dar fuoco a Roma, e poi perché non gli conveniva. Era la città che lui amava, aveva la forza del popolo per tenerla in suo potere perché questo, diversamente dai senatori, stava dalla sua parte. Poteva dar fuoco al popolo che gli garantiva il potere? Incendiando poi anche tante cose che amava: i suoi palazzi, le collezioni, lo stesso Circo Massimo. Le fonti ci dicono che anzi è tornato in fretta da Anzio, dove si trovava in quei giorni, per cercare di aiutare: aprì i suoi palazzi per accogliere gli sfollati. C’è poi un altro fatto cui si pensa poco: nessuno poteva immaginare che incendiando qualche palazzo avrebbe preso fuoco tutta la città”.

Alberto Angela ha dedicato una trilogia di libri all’incendio che ha devastato la città eterna: “Nerone colpevole? È stata la prima e più grande fake news della storia”

La Nazione, Firenze, 18 luglio 2023

Firenze, 18 luglio 2023 – Nella notte del 18 luglio del 64 d.C. scoppiò il grande incendio che ha cambiato per sempre la geografia di Roma e la nostra storia. Ma cosa accadde veramente quel giorno? E fu davvero responsabilità di Nerone? Alberto Angela, celebre divulgatore scientifico nonché paleontologo e naturalista, ha raccontato la catastrofe in una trilogia di libri dedicati all'ultimo imperatore della dinastia giulio-claudia. Un imperatore rappresentato col suo doppio volto: “Quello gioviale, di un ragazzo che oltre alla musica amava la velocità. Non c'erano le moto, ma Nerone andava con le quadriglie". E l'altra parte è quella feroce, cinica: "Uccide la madre, la moglie, fa uccidere tutti quelli che lo intralciano o che abbia il sospetto possano tramare contro di lui. È implacabile" racconta Angela. Ma poi ti accorgi che quando muore lui gli altri fanno di peggio. “Ricostruire l’incendio di Roma è come scrivere una detective story” spiega Angela. Solo che l’intrigo è ipotetico ancorché veritiero, e le prove sono in fumo da duemila anni. Contrariamente a quanto si pensi, Il 18 luglio del 64 d.C. si registra forse la prima e più grande fake news della storia: Roma brucia e l’imperatore è ritenuto responsabile. “È avvenuto nei due sensi – spiega Angela -. Nerone ha accusato ingiustamente i cristiani, e lui stesso è stato vittima di fake news per la storia, che lo ha dipinto come un principe nero, spietato. Ma né lui né i cristiani sono stati i responsabili dell’incendio. Gli storici sono concordi nel ritenere che il più grande incendio della storia di Roma sia stato un caso, avvenuto in condizioni precise: giornate caldissime, in una città che era quasi interamente fatta di legno. E soprattutto: l’innesco è avvenuto tra i magazzini del Circo Massimo, il più grande deposito di legna di Roma, di notte. Il giorno dopo soffiò il vento, e fu la fine. Roma bruciò per nove giorni. Roma era una città da un milione di abitanti. Gli incendi erano facilissimi: si stima che ogni dieci/quindici anni se ne registrasse uno molto grave. Di certo sappiamo che quello del 18 luglio è avvenuto di notte, in una zona che di giorno era molto frequentata, piena di negozi, mentre di notte diventava un bassofondo di Roma, popolato da prostitute, veggenti, pieno di bettole frequentate da ubriachi. Potrebbe essere stata una rissa”. Tutto ma non Nerone, insomma. “Innanzitutto – sottolinea Angela - perché non aveva motivo per dar fuoco a Roma, e poi perché non gli conveniva. Era la città che lui amava, aveva la forza del popolo per tenerla in suo potere perché questo, diversamente dai senatori, stava dalla sua parte. Poteva dar fuoco al popolo che gli garantiva il potere? Incendiando poi anche tante cose che amava: i suoi palazzi, le collezioni, lo stesso Circo Massimo. Le fonti ci dicono che anzi è tornato in fretta da Anzio, dove si trovava in quei giorni, per cercare di aiutare: aprì i suoi palazzi per accogliere gli sfollati. C’è poi un altro fatto cui si pensa poco: nessuno poteva immaginare che incendiando qualche palazzo avrebbe preso fuoco tutta la città”.

Unanimity at the (wrong) Nato summit edge: Biden the only leader who wore it correctly.

by Matteo Persivale, July 12, 2023

The "family photo" at the Vilnius summit highlighted another aspect of the leaders present: those who visit the tailor and those who prefer a cuff.

The laborious unanimity required by NATO procedures was also evident in the classic "family photo" at the Vilnius summit: nothing strategic, fortunately, but certainly in terms of menswear, the image is perplexing. The first to notice this, through social media, was men's fashion commentator Derek Guy, an American who, from his highly popular Twitter account @dieworkwear, pointed out to his 324 thousand followers that in the front row of the "family photo," the most powerful men in the Atlantic Alliance, except for one (Joe Biden, with the hem perfectly grazing his shoe), had glaringly incorrect pant hems, which were too long, not just by a few centimeters.

The sagging trouser hem at the ankle is a basic mistake that should always be avoided, especially in the last decade, which has seen a variation in the classic cut of suits – men's suits are cut closer to the body than they were twenty years ago, with jackets and pants being shorter. Furthermore, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, immune to the common rules of the "dress code," was, as always, wearing a light gray suit and brightly colored beige-to-orange shoes, along with his penchant for vibrant and decorated socks.

And let us draw a merciful veil over Giorgia Meloni's hem.

(note by me)

by Matteo Persivale, July 12, 2023

The "family photo" at the Vilnius summit highlighted another aspect of the leaders present: those who visit the tailor and those who prefer a cuff.

The laborious unanimity required by NATO procedures was also evident in the classic "family photo" at the Vilnius summit: nothing strategic, fortunately, but certainly in terms of menswear, the image is perplexing. The first to notice this, through social media, was men's fashion commentator Derek Guy, an American who, from his highly popular Twitter account @dieworkwear, pointed out to his 324 thousand followers that in the front row of the "family photo," the most powerful men in the Atlantic Alliance, except for one (Joe Biden, with the hem perfectly grazing his shoe), had glaringly incorrect pant hems, which were too long, not just by a few centimeters.

The sagging trouser hem at the ankle is a basic mistake that should always be avoided, especially in the last decade, which has seen a variation in the classic cut of suits – men's suits are cut closer to the body than they were twenty years ago, with jackets and pants being shorter. Furthermore, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, immune to the common rules of the "dress code," was, as always, wearing a light gray suit and brightly colored beige-to-orange shoes, along with his penchant for vibrant and decorated socks.

And let us draw a merciful veil over Giorgia Meloni's hem.

(note by me)

L’unanimità dell’orlo (sbagliato) al vertice Nato: Biden l’unico leader che lo portava in modo corretto

di Matteo Persivale, 12 luglio 2023

La «foto di famiglia» al vertice di Vilnius ha fatto risaltare anche un altro aspetto dei leader presenti: chi frequenta il sarto, e chi preferisce il risvoltino

La faticosa unanimità richiesta dalle procedure Nato è apparsa evidente anche nella classica «foto di famiglia» al vertice di Vilnius: niente di strategico, fortunatamente, ma certo in termini di menswear l’immagine lascia perplessi. Se n’è accorto per primo, tramite social media, il commentatore di moda maschile Derek Guy, americano, che dal suo popolarissimo account Twitter @dieworkwear ha fatto notare ai 324mila follower che nella prima fila della «foto di famiglia» gli uomini più potenti dell’Alleanza atlantica, tranne uno (Joe Biden, con l’orlo che andava perfettamente a sfiorare la scarpa), avevano l’orlo dei pantaloni clamorosamente sbagliato, troppo lungo e non soltanto di qualche centimetro.

Quello del pantalone afflosciato all’altezza della caviglia è un errore basilare che andrebbe sempre evitato, specialmente nell’ultimo decennio che ha visto il taglio classico degli abiti subire una variazione – l’abito maschile è tagliato più vicino al corpo di quanto lo fosse vent’anni fa, la giacca più corta, come la gamba dei pantaloni. Tra l’altro il premier canadese Justin Trudeau, immune alle comuni regole del «dress code», era come sempre in abito grigio chiaro e scarpe beige acceso tendente all’arancione, un suo vezzo insieme con quello dei calzini sgargianti e decorati.

E stendiamo un velo pietoso sull'orlo dei pantaloni della nostra Giorgia Meloni. (nota della sottoscritta)

di Matteo Persivale, 12 luglio 2023

La «foto di famiglia» al vertice di Vilnius ha fatto risaltare anche un altro aspetto dei leader presenti: chi frequenta il sarto, e chi preferisce il risvoltino

La faticosa unanimità richiesta dalle procedure Nato è apparsa evidente anche nella classica «foto di famiglia» al vertice di Vilnius: niente di strategico, fortunatamente, ma certo in termini di menswear l’immagine lascia perplessi. Se n’è accorto per primo, tramite social media, il commentatore di moda maschile Derek Guy, americano, che dal suo popolarissimo account Twitter @dieworkwear ha fatto notare ai 324mila follower che nella prima fila della «foto di famiglia» gli uomini più potenti dell’Alleanza atlantica, tranne uno (Joe Biden, con l’orlo che andava perfettamente a sfiorare la scarpa), avevano l’orlo dei pantaloni clamorosamente sbagliato, troppo lungo e non soltanto di qualche centimetro.

Quello del pantalone afflosciato all’altezza della caviglia è un errore basilare che andrebbe sempre evitato, specialmente nell’ultimo decennio che ha visto il taglio classico degli abiti subire una variazione – l’abito maschile è tagliato più vicino al corpo di quanto lo fosse vent’anni fa, la giacca più corta, come la gamba dei pantaloni. Tra l’altro il premier canadese Justin Trudeau, immune alle comuni regole del «dress code», era come sempre in abito grigio chiaro e scarpe beige acceso tendente all’arancione, un suo vezzo insieme con quello dei calzini sgargianti e decorati.

E stendiamo un velo pietoso sull'orlo dei pantaloni della nostra Giorgia Meloni. (nota della sottoscritta)

Did Romans discover America 15 centuries before Columbus??

July 2023

In recent days, a discovery was made at the archaeological site of Pompeii: a fresco depicting what, by all appearances, seems to be a pizza. This finding immediately sparked great curiosity and excitement, giving rise to a flurry of hypotheses. These range from the most outlandish ones, suggesting time travel in the style of "Indiana Jones and the Fate Quadrant," to more credible theories claiming that the depicted dish is a leavened focaccia, a precursor to modern pizza.

However, Italian students know very well about "Mense", a dish made of bread with food for two diners.

In the Aeneid, Virgil talks about "menses" when referring to a curse related to food, cast by the Harpy, the demon with the face of a woman and the horrifying appearance of a bird, against Aeneas and his men:

"Such hunger that you will even bite into the menses."

The term "menses" here refers to the bread disks that were distributed as plates at the beginning of banquets and later given as leftovers to the servants. Each mensa, used by two people, served in classical times to host and carve meat, thus becoming soaked with the juices and remains of the food. The menses were then distributed to the servants/poor.

In Italy, already in the 12th century, long before other countries, the bread mensa was replaced by the "tagliere," a wooden or terracotta disk shared by two diners.

It was only in the 1400s that the use of individual plates and glasses became widespread.

However, Italian students know very well about "Mense", a dish made of bread with food for two diners.

In the Aeneid, Virgil talks about "menses" when referring to a curse related to food, cast by the Harpy, the demon with the face of a woman and the horrifying appearance of a bird, against Aeneas and his men:

"Such hunger that you will even bite into the menses."

The term "menses" here refers to the bread disks that were distributed as plates at the beginning of banquets and later given as leftovers to the servants. Each mensa, used by two people, served in classical times to host and carve meat, thus becoming soaked with the juices and remains of the food. The menses were then distributed to the servants/poor.

In Italy, already in the 12th century, long before other countries, the bread mensa was replaced by the "tagliere," a wooden or terracotta disk shared by two diners.

It was only in the 1400s that the use of individual plates and glasses became widespread.

The case of the "Pompeii pizza" is not the first archaeological discovery with elements that seem historically and geographically out of place. Emblematic in this regard is the "Grotte Celloni mosaic," housed at the National Roman Museum in Palazzo Massimo in Rome. In this first-century AD mosaic floor artwork, a still life of fish, birds, and fruit is depicted. Notably, within the fruit basket, there appears to be what looks like a pineapple.

The problem is that the tropical fruit only reached European tables after the discovery of the Americas, more than 1300 years after the mosaic was created. Various hypotheses have been put forward about this artwork. Some argue that it is merely the image of a common pinecone adorned with leaves, while others believe that the representation of the exotic fruit is evidence of the Romans' arrival in the Americas and an ancient commercial link between Europe and the New World.

Some supporters of this thesis cite two other unique archaeological findings: the Comalcalco necropolis in the Gulf of Mexico and the "Pozzino Wreck," a Roman shipwreck sunk in the sea off the coast of Tuscany in the 2nd century BC.

At Comalcalco, several burials have been discovered inside jars and a series of clay brick constructions, both of which are typical of Mediterranean civilizations rather than Amerindian cultures.

In the "Pozzino Wreck," found in 1982 off the coast of Populonia, ampoules containing a range of medical products, including sunflower seeds, a plant native to the Americas and officially introduced to Europe after 1492, were found.

The hypothesis of transoceanic trade routes in antiquity and a possible Roman presence in America has long been supported by Elio Cadelo, an RAI journalist and science popularizer, author of the book "Quando i romani andavano in America. Scienza e conoscenze degli antichi navigatori"/"When the Romans Traveled to America: Science and Knowledge of Ancient Navigators".

"Archaeological and literary discoveries from classical times prove that the Romans visited America before Columbus," proclaims the introduction of the book. However, reading the book, one discovers that no "archaeological discovery" (once amateur excavators and artifacts of unknown origin found in America - or in Atlantis - are excluded) proves anything at all...

With these premises, one would say that it is better not to even open this book. But no. To demonstrate his eccentric thesis, the author had to lay the groundwork by reexamining what antiquity knew about astronomy, geography, and navigation. And here, he has done an excellent job. Probably summarizing from academic texts (the author of academic matters understands too little for this to be his own work), Cadelo has outlined an excellent picture of a body of knowledge that is certainly familiar to very few of us. To give just one example among many, Cadelo demonstrates, with quotes from ancient geographers in hand, that the ancients knew very well that the Earth was spherical (the "flat Earth" was only a geographical convention for drawing maps) and that they were adept at orienting themselves on the high seas (thus, it is not true that they mostly limited themselves to coastal navigation).

To support his theses, Cadelo takes us on a fascinating journey through the navigation tools and orientation techniques used by the ancients, some of which were sophisticated and incredibly simple at the same time.

In addition to this, Cadelo examines the knowledge related to the art of navigation in antiquity, extending his research to non-European civilizations, with equally fascinating and interesting results. This part, on its own, would have deserved a five-star rating because it opens up a world of information and data on a seemingly arid topic, which Cadelo manages to make interesting with his engaging style.

Unfortunately, in the concluding part, fortunately not very long, Cadelo abandons the safe anchor of academic sources and embarks on a fantasy-archeology venture in the style of Peter Kolosimo - as suggested by the title. The photo on the cover depicts, according to Cadelo, a Roman holding a pineapple in his hand. To me, it looks like a Roman holding either a bunch of grapes or a "sacculus," a small net for holding coins. But Cadelo is now in Kolosimo mode, shouting, "PINEAPPLES ARE AMONG US!" and assures that, since the late Roman art to which the figurine belongs was "absolutely realistic," it can only be a pineapple.

Reasoning like this shows where theories like Cadelo's come from: from a poor understanding of the subject matter. Cadelo, judging by the continuous mistakes in the citations in his book, is not familiar with Latin - and here and there, he even struggles with Italian syntax, which is not surprising considering he is a journalist for Rai. In fact, a distinctive characteristic of late Roman art, which will later evolve into Byzantine style, is the progressive loss of realism in favor of stylized, idealized renditions of depicted objects. No "absolute realism" there!

Among the countless other errors, I would like to point out that according to Cadelo, the Romans traded not only with China (which is historically well-documented by now) but also with New Zealand... which, however, was discovered and populated by the Maori only in the 10th century AD. Perhaps they engaged in trade with moa and codfish? Hmm!

To make a long story short, one should not be too picky and buy this book not for the thesis it supports but despite it. For 85%, it is an excursus on the science of navigation and geographical science in the ancient world, both of which were much more advanced than we might think (the recent discoveries about the functioning of the "Antikythera mechanism," for example, confirm the very high level these knowledges had reached). This part of the book contains, although interspersed with rather annoying syntactical "pearls" and downright whimsical theses, many useful and surprising pieces of information. Moreover, the author's arguments, "borrowed" from true experts, are often reliable. This part is, in short, decidedly fascinating, and reading it one learns many new things - at least new to us non-specialists.

It is only the concluding part - the one about "Pineapples are among us" - entirely the author's own creation, that can be easily skipped.

The problem is that the tropical fruit only reached European tables after the discovery of the Americas, more than 1300 years after the mosaic was created. Various hypotheses have been put forward about this artwork. Some argue that it is merely the image of a common pinecone adorned with leaves, while others believe that the representation of the exotic fruit is evidence of the Romans' arrival in the Americas and an ancient commercial link between Europe and the New World.

Some supporters of this thesis cite two other unique archaeological findings: the Comalcalco necropolis in the Gulf of Mexico and the "Pozzino Wreck," a Roman shipwreck sunk in the sea off the coast of Tuscany in the 2nd century BC.

At Comalcalco, several burials have been discovered inside jars and a series of clay brick constructions, both of which are typical of Mediterranean civilizations rather than Amerindian cultures.

In the "Pozzino Wreck," found in 1982 off the coast of Populonia, ampoules containing a range of medical products, including sunflower seeds, a plant native to the Americas and officially introduced to Europe after 1492, were found.

The hypothesis of transoceanic trade routes in antiquity and a possible Roman presence in America has long been supported by Elio Cadelo, an RAI journalist and science popularizer, author of the book "Quando i romani andavano in America. Scienza e conoscenze degli antichi navigatori"/"When the Romans Traveled to America: Science and Knowledge of Ancient Navigators".

"Archaeological and literary discoveries from classical times prove that the Romans visited America before Columbus," proclaims the introduction of the book. However, reading the book, one discovers that no "archaeological discovery" (once amateur excavators and artifacts of unknown origin found in America - or in Atlantis - are excluded) proves anything at all...

With these premises, one would say that it is better not to even open this book. But no. To demonstrate his eccentric thesis, the author had to lay the groundwork by reexamining what antiquity knew about astronomy, geography, and navigation. And here, he has done an excellent job. Probably summarizing from academic texts (the author of academic matters understands too little for this to be his own work), Cadelo has outlined an excellent picture of a body of knowledge that is certainly familiar to very few of us. To give just one example among many, Cadelo demonstrates, with quotes from ancient geographers in hand, that the ancients knew very well that the Earth was spherical (the "flat Earth" was only a geographical convention for drawing maps) and that they were adept at orienting themselves on the high seas (thus, it is not true that they mostly limited themselves to coastal navigation).

To support his theses, Cadelo takes us on a fascinating journey through the navigation tools and orientation techniques used by the ancients, some of which were sophisticated and incredibly simple at the same time.

In addition to this, Cadelo examines the knowledge related to the art of navigation in antiquity, extending his research to non-European civilizations, with equally fascinating and interesting results. This part, on its own, would have deserved a five-star rating because it opens up a world of information and data on a seemingly arid topic, which Cadelo manages to make interesting with his engaging style.

Unfortunately, in the concluding part, fortunately not very long, Cadelo abandons the safe anchor of academic sources and embarks on a fantasy-archeology venture in the style of Peter Kolosimo - as suggested by the title. The photo on the cover depicts, according to Cadelo, a Roman holding a pineapple in his hand. To me, it looks like a Roman holding either a bunch of grapes or a "sacculus," a small net for holding coins. But Cadelo is now in Kolosimo mode, shouting, "PINEAPPLES ARE AMONG US!" and assures that, since the late Roman art to which the figurine belongs was "absolutely realistic," it can only be a pineapple.

Reasoning like this shows where theories like Cadelo's come from: from a poor understanding of the subject matter. Cadelo, judging by the continuous mistakes in the citations in his book, is not familiar with Latin - and here and there, he even struggles with Italian syntax, which is not surprising considering he is a journalist for Rai. In fact, a distinctive characteristic of late Roman art, which will later evolve into Byzantine style, is the progressive loss of realism in favor of stylized, idealized renditions of depicted objects. No "absolute realism" there!

Among the countless other errors, I would like to point out that according to Cadelo, the Romans traded not only with China (which is historically well-documented by now) but also with New Zealand... which, however, was discovered and populated by the Maori only in the 10th century AD. Perhaps they engaged in trade with moa and codfish? Hmm!

To make a long story short, one should not be too picky and buy this book not for the thesis it supports but despite it. For 85%, it is an excursus on the science of navigation and geographical science in the ancient world, both of which were much more advanced than we might think (the recent discoveries about the functioning of the "Antikythera mechanism," for example, confirm the very high level these knowledges had reached). This part of the book contains, although interspersed with rather annoying syntactical "pearls" and downright whimsical theses, many useful and surprising pieces of information. Moreover, the author's arguments, "borrowed" from true experts, are often reliable. This part is, in short, decidedly fascinating, and reading it one learns many new things - at least new to us non-specialists.

It is only the concluding part - the one about "Pineapples are among us" - entirely the author's own creation, that can be easily skipped.