This year's topic for the Settimana della Lingua Italiana nel Mondo (Oct. 16 to 21, 2023) is

Italian and Sustainability.

2023 also marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of our great author Italo Calvino. That gave us the idea to create a contest for students based on Calvino's work (he was an ante litteram "green" author ) and the theme of sustainability.

Please read the attached document and consider having one of your classes take part in the contest. As you will see, the works the students are encouraged to produce can have a variety of formats so that they can choose the one which best suits their learning styles.

All works must be submitted to this office in digital form by Oct 13, which is the week before the

Settimana della Lingua Italiana nel Mondo.

There will be prizes for the best works and formal recognition by the Consulate for all participants!

Kindly let me know whether one of your classes or individual students will be participating in the contest.

Please feel free to write to me for any further information or clarification.

Best wishes for a great academic year 2023/24!

Patrizia

______________________________________________

Patrizia Calanchini Monti

Dirigente Ufficio Istruzione - Director of Education Office

Consolato Generale d'Italia - Consulate General of Italy

Public Ledger Building, Suite 956

600 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19106

Phone (267) 608 0690

http://www.filadelfia.esteri.it

email [email protected]

Dirigente Ufficio Istruzione - Director of Education Office

Consolato Generale d'Italia - Consulate General of Italy

Public Ledger Building, Suite 956

600 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19106

Phone (267) 608 0690

http://www.filadelfia.esteri.it

email [email protected]

CONTEST

THE ITALIAN WRITER ITALO CALVINO AND THE THEME OF SUSTAINABILITY

The year 2023 presents two co-occurring events: In October, the 23rd edition of the “Settimana della Lingua Italiana nel Mondo” will focus on the theme of “Italian and Sustainability.” The selected theme aligns with the UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development and the bid for EXPO 2030 Rome (People and territories. Regeneration, inclusion and innovation). In addition, the year 2023 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of renowned Italian author Italo Calvino. In recognition of Italy’s position at the forefront of environmental issues in the world, we therefore propose a school writing contest that combines these two occurrences and in doing so promotes a culture of sustainability as expressed through the Italian language.

THE ITALIAN WRITER ITALO CALVINO AND THE THEME OF SUSTAINABILITY

The year 2023 presents two co-occurring events: In October, the 23rd edition of the “Settimana della Lingua Italiana nel Mondo” will focus on the theme of “Italian and Sustainability.” The selected theme aligns with the UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development and the bid for EXPO 2030 Rome (People and territories. Regeneration, inclusion and innovation). In addition, the year 2023 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of renowned Italian author Italo Calvino. In recognition of Italy’s position at the forefront of environmental issues in the world, we therefore propose a school writing contest that combines these two occurrences and in doing so promotes a culture of sustainability as expressed through the Italian language.

CONTEST

Select one short story or part of a novel by Italo Calvino among the ones from which the following extracts have been taken and introduce it to the class. Focus on the selected quotations and/or other passages from Calvino’s works and have the students create an original piece summarizing/commenting on the “green” themes in Calvino.

Students’ works might be in one of the following formats:

Students of the same class can select different formats for their submissions. Students may work individually or in groups.

In the case of group work, every member of the group should be responsible for part of the work (for example, in the case of a narrated power point presentation, one student will be responsible for selecting (or drawing) the images, one student will coordinate writing the Italian text, one student will revise the language to make sure it is accurate in terms of lexis, grammar and syntax, one student will record their voice for the narration, and so on).

Select one short story or part of a novel by Italo Calvino among the ones from which the following extracts have been taken and introduce it to the class. Focus on the selected quotations and/or other passages from Calvino’s works and have the students create an original piece summarizing/commenting on the “green” themes in Calvino.

Students’ works might be in one of the following formats:

- Comic strip telling a short story with speech balloons in Italian (min. 8/max 12 cartoons)

- Power point presentation including pictures and text in Italian (min 6 max 10).

- Narrated presentation (slide show of a power point presentation with a narrating voice in Italian - min 6 max 10).

- Short video in the form of a sketch, short scene, with dialogues written and acted out by the students in Italian (min 1minutes max 3 minutes).

- Short prose in Italian based on one of Calvino’s stories (min.500 - max 1000 words).

- Short poem in Italian based on one of Calvino's stories (at least four stanzas of three or four lines each - can be rhymed or not).

Students of the same class can select different formats for their submissions. Students may work individually or in groups.

In the case of group work, every member of the group should be responsible for part of the work (for example, in the case of a narrated power point presentation, one student will be responsible for selecting (or drawing) the images, one student will coordinate writing the Italian text, one student will revise the language to make sure it is accurate in terms of lexis, grammar and syntax, one student will record their voice for the narration, and so on).

Brief introduction to Calvino’s work and “green” themesBorn in Cuba, raised in Sanremo (Liguria) and resided in Turin, Paris, and Rome, Italo Calvino is certainly one of the best-known and best-loved twentieth century Italian writers in the world, a model of invention and style for clarity of writing and inexhaustible imagination. The son of two environmental scientists - his father was a famous agronomist, his mother a distinguished botanist - Italo was educated from an early age to a worldview that today we would describe as total ecology, whereby the human being is first and foremost one species on the planet - fundamental and unique, but still one of the countless species that populate the earth.

Although his production dates back to the period between the 1960s and the 1980s (he died in 1985 before terms such as "climate change” and “resource depletion" became part of the everyday lexicon), Calvino was well aware of the rift between nature and man that was being consumed by human behaviors and of the irreparable damage that mankind was creating and would create more and more massively in the future. Environmental issues are a common theme in many of Italo Calvino's works. However, thanks to their fairy-tale tone and their imaginary settings that are often far removed from the common sense of space and time, Calvino’s stories are both entertaining and reflective, and the deeper meaning of environmental education is indirectly addressed in a way that is never boring or superficial. Using a light tone, irony and imagination, Calvino turns every hierarchy upside down and brings complex issues within the reach of everyone. Imaginary worlds and distant eras provide a fantastic background to narrate with playfulness, but also with detailed realism, themes that were dear to him such as man's relationship with nature, urban disaster, pollution, and the alienation of the individual in increasingly industrialized cities.

Quotations from Calvino’s work:

Although his production dates back to the period between the 1960s and the 1980s (he died in 1985 before terms such as "climate change” and “resource depletion" became part of the everyday lexicon), Calvino was well aware of the rift between nature and man that was being consumed by human behaviors and of the irreparable damage that mankind was creating and would create more and more massively in the future. Environmental issues are a common theme in many of Italo Calvino's works. However, thanks to their fairy-tale tone and their imaginary settings that are often far removed from the common sense of space and time, Calvino’s stories are both entertaining and reflective, and the deeper meaning of environmental education is indirectly addressed in a way that is never boring or superficial. Using a light tone, irony and imagination, Calvino turns every hierarchy upside down and brings complex issues within the reach of everyone. Imaginary worlds and distant eras provide a fantastic background to narrate with playfulness, but also with detailed realism, themes that were dear to him such as man's relationship with nature, urban disaster, pollution, and the alienation of the individual in increasingly industrialized cities.

Quotations from Calvino’s work:

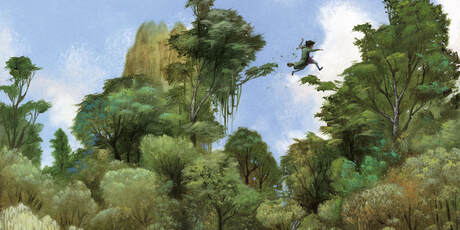

Il Barone rampante (The Baron in the Trees)This story tells of a 12-year-old teenager, Cosimo, son of the baron of a village in Liguria, who, tired of life full of rules and constraints, decides, as a sign of protest, to go live in the trees and never come down again. Thus he begins a new life full of adventures as he continues to live in trees and becomes better and better at moving quickly from branch to branch, which is symbolic of the search for harmony with Nature.

Il Barone rampante states the importance of finding a different point of view and of learning to recognize the obsolete mechanisms of our society that force us to reiterate wrong and harmful behaviors. Man oppressed by the rules of everyday life wants to escape and climbs trees,

‘Il cielo è vuoto, e a noi vecchi d’Ombrosa, abituati a vivere sotto quelle verdi cupole, fa male agli occhi guardarlo. Si direbbe che gli alberi non hanno retto, dopo che gli uomini sono stati presi dalla furia della scure [. ] Ombrosa non c’è più’”

“Ora, già non si riconoscono più, queste contrade. S’è cominciato quando vennero i Francesi, a tagliar boschi come fossero prati che si falciano tutti gli anni e poi ricrescono. Non sono ricresciuti. Pareva una cosa della guerra, di Napoleone, di quei tempi: invece non si smise più. I dossi sono nudi che a guardarli, noi che li conoscevamo da prima, fa impressione. “(577)

“Allora, dovunque s’andasse, avevamo sempre rami e fronde tra noi e il cielo. L’unica zona di vegetazione più bassa erano i limoneti, ma anche là in mezzo si levavano contorti gli alberi di fico, che più a monte ingombravano tutto il cielo degli orti, con le cupole del pesante loro fogliame, e se non erano fichi erano ciliegi dalle brune fronde, o più teneri cotogni, peschi, mandorli, giovani peri, prodighi susini, e poi sorbi, carrubi, quando non era un gelso o un noce annoso. Finiti gli orti, cominciava l’oliveto, grigio-argento, una nuvola che sbiocca a mezza costa. In fondo c’era il paese accatastato […] ed anche lì, tra i tetti, un continuo spuntare di chiome di piante: lecci, platani, anche roveri, una vegetazione disinteressata e altera […]. Sopra gli olivi cominciava il bosco.

I pini dovevano un tempo aver regnato su tutta la plaga, perché ancora s’infiltravano in lami e ciuffi di bosco giù per i versanti fino alla spiaggia del mare, e così i larici. Le roveri erano più frequenti e fitte di quanto oggi non sembri, perché furono la prima e più pregiata vittima della scure. Più in su i pini cedevano ai castagni, il bosco saliva la montagna e non se ne vedevano i confini. Questo era l’universo di linfa entro il quale noi vivevamo, abitanti d’Ombrosa, quasi senza accorgercene.” (577–78)

The richness and precision with which Calvin describes vegetation in detail leaves no doubt about the importance of trees in his narrative. This is not a decorative description or a symbolic backdrop for the narrative; the trees are real protagonists and their felling a great tragedy.

Il Barone rampante states the importance of finding a different point of view and of learning to recognize the obsolete mechanisms of our society that force us to reiterate wrong and harmful behaviors. Man oppressed by the rules of everyday life wants to escape and climbs trees,

‘Il cielo è vuoto, e a noi vecchi d’Ombrosa, abituati a vivere sotto quelle verdi cupole, fa male agli occhi guardarlo. Si direbbe che gli alberi non hanno retto, dopo che gli uomini sono stati presi dalla furia della scure [. ] Ombrosa non c’è più’”

“Ora, già non si riconoscono più, queste contrade. S’è cominciato quando vennero i Francesi, a tagliar boschi come fossero prati che si falciano tutti gli anni e poi ricrescono. Non sono ricresciuti. Pareva una cosa della guerra, di Napoleone, di quei tempi: invece non si smise più. I dossi sono nudi che a guardarli, noi che li conoscevamo da prima, fa impressione. “(577)

“Allora, dovunque s’andasse, avevamo sempre rami e fronde tra noi e il cielo. L’unica zona di vegetazione più bassa erano i limoneti, ma anche là in mezzo si levavano contorti gli alberi di fico, che più a monte ingombravano tutto il cielo degli orti, con le cupole del pesante loro fogliame, e se non erano fichi erano ciliegi dalle brune fronde, o più teneri cotogni, peschi, mandorli, giovani peri, prodighi susini, e poi sorbi, carrubi, quando non era un gelso o un noce annoso. Finiti gli orti, cominciava l’oliveto, grigio-argento, una nuvola che sbiocca a mezza costa. In fondo c’era il paese accatastato […] ed anche lì, tra i tetti, un continuo spuntare di chiome di piante: lecci, platani, anche roveri, una vegetazione disinteressata e altera […]. Sopra gli olivi cominciava il bosco.

I pini dovevano un tempo aver regnato su tutta la plaga, perché ancora s’infiltravano in lami e ciuffi di bosco giù per i versanti fino alla spiaggia del mare, e così i larici. Le roveri erano più frequenti e fitte di quanto oggi non sembri, perché furono la prima e più pregiata vittima della scure. Più in su i pini cedevano ai castagni, il bosco saliva la montagna e non se ne vedevano i confini. Questo era l’universo di linfa entro il quale noi vivevamo, abitanti d’Ombrosa, quasi senza accorgercene.” (577–78)

The richness and precision with which Calvin describes vegetation in detail leaves no doubt about the importance of trees in his narrative. This is not a decorative description or a symbolic backdrop for the narrative; the trees are real protagonists and their felling a great tragedy.

Le città Invisibili (Invisible Cities)

Le Città Invisibili certainly best represents the author's sensitivity to environmental issues. Released in 1972, when environmentalism was in its infancy, it has kept all its evocative power intact over the decades.

The volume consists of nine chapters, each of which opens and closes with a dialogue between Marco Polo and the Tatar emperor Kublai Khan who asks the explorer about the cities of his immense empire. Each chapter contains five descriptions of the cities visited by Marco Polo, except the first and last chapters, which contain ten descriptions. In all, fifty-five cities, each one with a woman's name, mysterious and highly significant.

The relationship between cities and their surroundings is certainly the theme, the thread of the narrative that is most striking in its contemporaneity and even its ability to anticipate current debate.

Quotes

“La città di Leonia rifà se stessa tutti i giorni: ogni mattina la popolazione si risveglia tra lenzuola fresche, si lava con saponette appena sgusciate dall’involucro, indossa vestaglie nuove fiammanti, estrae dal più perfezionato frigorifero barattoli di latta ancora intonsi, ascoltando le ultime filastrocche che dall’ultimo modello d’apparecchio.”

The consequence is obvious and inevitable:

“Sui marciapiedi, avviluppati in tersi sacchi di plastica, i resti della Leonia d’ieri aspettano il carro dello spazzaturaio. Non solo tubi di dentifricio schiacciati, lampadine fulminate, giornali, contenitori, materiali d’imballaggio, ma anche scaldabagni, enciclopedie, pianoforti, servizi di porcellana: […] l’opulenza di Leonia si misura dalle cose che ogni giorno vengono buttate via per far posto alle nuove.”

The theme is one of continuous waste, of uncontrolled consumerism.

And no one seems to care about the consequences of their actions (“dove portino ogni giorno il loro carico gli spazzaturai nessuno se lo chiede” - "no one asks where the garbage men take their loads every day”). The result is a world overrun with piles of garbage, which the city continuously produces.

The city of Leonia is a metaphor for our throwaway society and of its inability to solve the problem of matter consumed and accumulated in a never-ending and unnatural process, in which the rule of "nothing is created, and nothing is destroyed" is broken. Too much is created; and of all this, too little is recycled, nor can be destroyed.

Le Città Invisibili certainly best represents the author's sensitivity to environmental issues. Released in 1972, when environmentalism was in its infancy, it has kept all its evocative power intact over the decades.

The volume consists of nine chapters, each of which opens and closes with a dialogue between Marco Polo and the Tatar emperor Kublai Khan who asks the explorer about the cities of his immense empire. Each chapter contains five descriptions of the cities visited by Marco Polo, except the first and last chapters, which contain ten descriptions. In all, fifty-five cities, each one with a woman's name, mysterious and highly significant.

The relationship between cities and their surroundings is certainly the theme, the thread of the narrative that is most striking in its contemporaneity and even its ability to anticipate current debate.

Quotes

“La città di Leonia rifà se stessa tutti i giorni: ogni mattina la popolazione si risveglia tra lenzuola fresche, si lava con saponette appena sgusciate dall’involucro, indossa vestaglie nuove fiammanti, estrae dal più perfezionato frigorifero barattoli di latta ancora intonsi, ascoltando le ultime filastrocche che dall’ultimo modello d’apparecchio.”

The consequence is obvious and inevitable:

“Sui marciapiedi, avviluppati in tersi sacchi di plastica, i resti della Leonia d’ieri aspettano il carro dello spazzaturaio. Non solo tubi di dentifricio schiacciati, lampadine fulminate, giornali, contenitori, materiali d’imballaggio, ma anche scaldabagni, enciclopedie, pianoforti, servizi di porcellana: […] l’opulenza di Leonia si misura dalle cose che ogni giorno vengono buttate via per far posto alle nuove.”

The theme is one of continuous waste, of uncontrolled consumerism.

And no one seems to care about the consequences of their actions (“dove portino ogni giorno il loro carico gli spazzaturai nessuno se lo chiede” - "no one asks where the garbage men take their loads every day”). The result is a world overrun with piles of garbage, which the city continuously produces.

The city of Leonia is a metaphor for our throwaway society and of its inability to solve the problem of matter consumed and accumulated in a never-ending and unnatural process, in which the rule of "nothing is created, and nothing is destroyed" is broken. Too much is created; and of all this, too little is recycled, nor can be destroyed.

Marcovaldo ovvero Le stagioni in città (Marcovaldo: or the Seasons in the City)

Marcovaldo ovvero Le stagioni in città is a collection of twenty short stories.

The stories are set in a large unspecified city that is symbolic of every city, with concrete, smokestacks, skyscrapers and traffic, and Marcovaldo is its typical citizen. The Sbav company, at which Marcovaldo works, is also the quintessential company, a symbol of all companies, and precisely because of this we know neither what is produced there, nor what is sold there, nor the contents of the packaging that the protagonist moves and transports all day long.

In Marcovaldo, Calvino combines fairy-tale aspects and irony to address current themes and issues: chaotic city life, urbanization without rationality and order, increasing industrialization and poverty of the lower segments of the population, and the difficulty of human and interpersonal relationships.

Quotes

“il formaggio era fatto di materia plastica, il burro con le candele steariche, nella frutta e verdura l’arsenico degli insetticidi era concentrato in percentuali più forti che non le vitamine, i polli per ingrassarli li imbottivano di certe pillole sintetiche che potevano trasformare in pollo chi ne mangiava un cosciotto. Il pesce fresco era stato pescato l’anno scorso in Islanda e gli truccavano gli occhi perché sembrasse di ieri. Da certe bottiglie di latte era saltato fuori un sorcio non si sa se vivo o morto. Da quelle d’olio non colava il dorato succo dell’oliva, ma grasso di vecchi muli, opportunamente distillato”

“Il vento, venendo in città da lontano, le porta doni inconsueti, di cui s'accorgono solo poche anime sensibili, come i raffreddati del fieno, che starnutano per pollini di fiori d'altre terre”.

“Marcovaldo sentiva la neve come amica, come un elemento che annullava la gabbia di muri in cui era imprigionata la sua vita.

Marcovaldo ovvero Le stagioni in città is a collection of twenty short stories.

The stories are set in a large unspecified city that is symbolic of every city, with concrete, smokestacks, skyscrapers and traffic, and Marcovaldo is its typical citizen. The Sbav company, at which Marcovaldo works, is also the quintessential company, a symbol of all companies, and precisely because of this we know neither what is produced there, nor what is sold there, nor the contents of the packaging that the protagonist moves and transports all day long.

In Marcovaldo, Calvino combines fairy-tale aspects and irony to address current themes and issues: chaotic city life, urbanization without rationality and order, increasing industrialization and poverty of the lower segments of the population, and the difficulty of human and interpersonal relationships.

Quotes

“il formaggio era fatto di materia plastica, il burro con le candele steariche, nella frutta e verdura l’arsenico degli insetticidi era concentrato in percentuali più forti che non le vitamine, i polli per ingrassarli li imbottivano di certe pillole sintetiche che potevano trasformare in pollo chi ne mangiava un cosciotto. Il pesce fresco era stato pescato l’anno scorso in Islanda e gli truccavano gli occhi perché sembrasse di ieri. Da certe bottiglie di latte era saltato fuori un sorcio non si sa se vivo o morto. Da quelle d’olio non colava il dorato succo dell’oliva, ma grasso di vecchi muli, opportunamente distillato”

“Il vento, venendo in città da lontano, le porta doni inconsueti, di cui s'accorgono solo poche anime sensibili, come i raffreddati del fieno, che starnutano per pollini di fiori d'altre terre”.

“Marcovaldo sentiva la neve come amica, come un elemento che annullava la gabbia di muri in cui era imprigionata la sua vita.

La nuvola di smog (The smog)

The protagonist of La Nuvola di Smog, with no name or face, is a bachelor intellectual who travels to a city to work as an editor at "The Purification," a magazine of the EPAUCI (Urban Atmosphere Purification Corporation of Industrial Centers). The city in question is in fact surrounded by a great cloud of smog, visible everywhere: there is dust in the room rented by the protagonist, in his office and on his clothes, on the walls and streets, in the air and on his skin.

The atmosphere is thus literally and figuratively polluted: everywhere the cloud of smog makes its heavy presence felt. Inhabitants fit perfectly into the absurd and repetitive landscape.

However, the smog cloud is not just an environmentalist tale. Moving from a more literal interpretation to a more allegorical one, we understand that the cloud is symbolic of the evil of living to which the new urban and industrialized society exposes us, which is based on the trauma of losing our relationship with nature. The tale places great emphasis on human responses to this sad condition.

Quotes

“Contro le più catastrofiche profezie sulla civiltà industriale, noi riaffermiamo che non vi sarà (né d’altronde vi è mai stata) contraddizione tra un’economia in libera naturale espansione e l’igiene necessaria all’organismo umano, […] tra il fumo delle nostre operose ciminiere e l’azzurro e il verde delle nostre incomparabili bellezze naturali”

“Quelle facciate di case annerite, quei vetri opachi, quei davanzali a cui non ci si poteva appoggiare, quei visi umani quasi cancellati, quella foschia che ora col progredire dell’autunno perdeva il suo umido sentore di intemperie e diventava come una qualità degli oggetti, come se ognuno e ogni cosa avesse di giorno in giorno meno forma, meno senso e valore, tutto quel che per me era sostanza di una miseria generale, per gli uomini come lui doveva essere segno di ricchezza, supremazia e potenza, e insieme di pericolo, distruzione e tragedia, un modo per sentirsi investiti, a stare lì sospesi, d’una grandezza eroica.”

“Un’ombra di sporco che la insudiciava tutta e ne mutava […] pure la consistenza, perché era greve, non ben spiccicata dalla terra, dalla distesa screziata della città sulla quale pure scorreva lentamente, a poco a poco cancellandola da una parte e ricoprendola dall’altra, ma lasciandosi dietro uno strascico come di filacce un po ’sudice, che non finivano mai”.

“D’improvviso contro il buio di fuori la vetrata apparve ricoperta d’un minuto smeriglio, certo fatto di polvere di ghisa, luccicante come il pulviscolo d’una galassia. Il disegno delle ombre là fuori si scompose; più nette risultarono in fondo le sagome delle ciminiere, incappucciate ciascuna da uno sbuffo rosso, e sopra queste fiamme per contrasto s’accentuava l’ala nera come d’inchiostro che invadeva tutto il cielo e vi si scorgeva salire e vorticare punti incandescenti. “

The protagonist of La Nuvola di Smog, with no name or face, is a bachelor intellectual who travels to a city to work as an editor at "The Purification," a magazine of the EPAUCI (Urban Atmosphere Purification Corporation of Industrial Centers). The city in question is in fact surrounded by a great cloud of smog, visible everywhere: there is dust in the room rented by the protagonist, in his office and on his clothes, on the walls and streets, in the air and on his skin.

The atmosphere is thus literally and figuratively polluted: everywhere the cloud of smog makes its heavy presence felt. Inhabitants fit perfectly into the absurd and repetitive landscape.

However, the smog cloud is not just an environmentalist tale. Moving from a more literal interpretation to a more allegorical one, we understand that the cloud is symbolic of the evil of living to which the new urban and industrialized society exposes us, which is based on the trauma of losing our relationship with nature. The tale places great emphasis on human responses to this sad condition.

Quotes

“Contro le più catastrofiche profezie sulla civiltà industriale, noi riaffermiamo che non vi sarà (né d’altronde vi è mai stata) contraddizione tra un’economia in libera naturale espansione e l’igiene necessaria all’organismo umano, […] tra il fumo delle nostre operose ciminiere e l’azzurro e il verde delle nostre incomparabili bellezze naturali”

“Quelle facciate di case annerite, quei vetri opachi, quei davanzali a cui non ci si poteva appoggiare, quei visi umani quasi cancellati, quella foschia che ora col progredire dell’autunno perdeva il suo umido sentore di intemperie e diventava come una qualità degli oggetti, come se ognuno e ogni cosa avesse di giorno in giorno meno forma, meno senso e valore, tutto quel che per me era sostanza di una miseria generale, per gli uomini come lui doveva essere segno di ricchezza, supremazia e potenza, e insieme di pericolo, distruzione e tragedia, un modo per sentirsi investiti, a stare lì sospesi, d’una grandezza eroica.”

“Un’ombra di sporco che la insudiciava tutta e ne mutava […] pure la consistenza, perché era greve, non ben spiccicata dalla terra, dalla distesa screziata della città sulla quale pure scorreva lentamente, a poco a poco cancellandola da una parte e ricoprendola dall’altra, ma lasciandosi dietro uno strascico come di filacce un po ’sudice, che non finivano mai”.

“D’improvviso contro il buio di fuori la vetrata apparve ricoperta d’un minuto smeriglio, certo fatto di polvere di ghisa, luccicante come il pulviscolo d’una galassia. Il disegno delle ombre là fuori si scompose; più nette risultarono in fondo le sagome delle ciminiere, incappucciate ciascuna da uno sbuffo rosso, e sopra queste fiamme per contrasto s’accentuava l’ala nera come d’inchiostro che invadeva tutto il cielo e vi si scorgeva salire e vorticare punti incandescenti. “